A while back Chris Pruett (creator of the excellent Chris’s Survival Horror Quest and currently at work with some creepy stuff at Robot Invader) and I had some discussion about common horror / puzzle tropes over twitter. Now all of these little nuggets, and more that came up during subsequent mail discussions, have been collected into a nice blog post by Chris. If you are ever going to make a survival horror please read this first. Here comes:

Puzzles

No puzzles about equalizing pressure (or any other type of dial) by adjusting switches or knobs. Do not include puzzles that involve reconnecting the power, especially to an elevator. No sliding bookshelves with scratch marks on the floor. Avoid puzzles that involve pressing keys on a piano in a specific order. Do not require the player to collect paintings to reveal a secret image, or examine paintings to decode a correct sequence of buttons. No locked doors with an engraved symbol that also appears on the key. No important documents encrypted with stupid-simple substitution ciphers.

As you design, repeat this mantra to yourself: “I will have no keycard doors in my game.” No feeding fertilizer or poison to giant plants. Check yourself before adding puzzles about inserting crystals, gems, or figurines into some ornate locking mechanism. Reconsider any puzzle involving a four-digit number sequence, found elsewhere, that opens a lock.

Do not employ sliding block puzzles. Ever. That includes sliding statues! No!

Deny the urge to take inventory items away from the player without a legitimate reason. When building puzzles that require combining more than two items, you must allow combination of arbitrary pairs of items even before the entire set has been collected.

Do not turn terrifying monsters into puzzles unless your goal is to kill all tension.

It’s important to make objectives and mechanics clear, but if you just tell the player what to do and where to go, you’ve removed the puzzle entirely. Let them think for themselves occasionally. Be especially vigilant when designing any cumbersome door opening apparatus. Remember, your players will only believe so much!

Story

Not all stories have to be about the protagonist’s personal demons. Don’t blame everything on evil mega-corporations. You don’t need a crazy Special Forces unit with an awkward acronym name. Do not include a sequence in which a child must crawl through a small opening to unlock a door for an adult. No more helicopters escaping from mushroom-cloud explosions. Eschew underdeveloped sub-plots about drugs.

Avoid zombies. But if you must use zombies, for the love of all that is holy, do not rely on a virus to explain them. Zombie dogs: no.

Not all vengeful ghosts need to be women. And curses do not all need to spread like a virus. And the virus doesn’t have to kill its victims after exactly seven days. Also, ghosts don’t always have to be innocent people who died horrible deaths.

It’s not very believable that a high-security military research complex would have passwords written down on scraps of paper. If your plot twist involves the surprise reveal of a secret, sinister cult, you should probably stop.

Try to think of ways to put your characters in vulnerable situations that are not limited to making all of your characters petite school girls. Men can be vulnerable too. Plus, I know some school girls that could wipe the floor with your sorry designer ass.

Levels and Characters

There are other ways to block a passage off than having the roof collapse. Make a distinction between locked doors that will eventually open and doors that can never be opened; if you have any of the former, the latter must be barred, or broken, or otherwise obviously forever inaccessible. Be warned, however, that “it’s jammed” gets old mighty quick.

No arbitrarily non-interactive objects; either you can interact with all doors or none of them. Ensure that you have more doors that can be opened than cannot. Do not block the player with short fences or other obstacles that should be trivial to bypass.

If a location is supposed to carry emotional weight, do not litter it with ammo boxes and collectibles. Do you want the player to contemplate the horrible living conditions of a young child or rummage through their things looking for loot?

Just say “No!” to items that are of great use to the player’s problems but cannot be picked up. No obstacles that could be easily dispatched using the protagonist’s arsenal but instead require some puzzle sequence to overcome. Do not provide a stock of limited supplies unless you make the remaining amount clear. Do not put hidden collectables in horror games with large levels, or in games that do not allow you to backtrack. Maybe just skip the whole hidden collectable thing completely.

We don’t need any more tentacle monsters in horror games. Especially not tentacle monsters with bright, bulbous weak spots. Avoid close-quarter combat with ghosts that can pass through walls. Never throw the player against a source of infinite damage unless you also provide a source of infinite health and ammo (e.g. infinite enemy spawner).

Little known fact: not all monsters have an irresistible urge to bare their teeth and scream at the player. Nor do they all hunch over with long, bent arms. Crazy, huh!?

Excepting certain types of zombie, it is almost never exciting to see a monster charge the protagonist. Perhaps you can modify your AI to stalk the player and approach him slowly to appear more menacing? Caveat: circling the player and occasionally revealing a weak spot is not a good alternative.

Ask yourself: “how many times have I been to the gym this year?” You’re a game designer, so the answer is probably “none.” Do you think your game’s cultists have it any better? They’re too busy summoning an obscure deity to think about their diety. So why did you make them look like they’re all bodybuilders and/or silicon implant models?

And while we’re on the topic of appearances, does your monster really need that awkward underwear? I mean, you just had him rip a dude’s head off in the last scene; I don’t think your audience is going to be phased by a little monster nudity. Or heck, just come up with something else. Tiny bits of torn fabric around the midsection of an otherwise naked beast is a cop-out.

Technical Stuff

When you have a body lying on the floor that is significantly more detailed than all of the other bodies on the floor, we all know that it’ll come to life and attack us sooner or later. Also, a surprise attack isn’t very surprising if the game suddenly starts loading like crazy moments before.

Do not put scary encounters in cutscenes. I know, I know, you want to control the camera and the timing and the sound so everything is “just right.” But listen, games don’t work that way. Take a gamble. Let the player discover the monster through gameplay.

Navigating save slots, confirming file overwrites, and waiting for flashy menu animations is pretty much the worst possible thing you can subject a player to. Your sense of presence must extend to the game as a whole, even your UI.

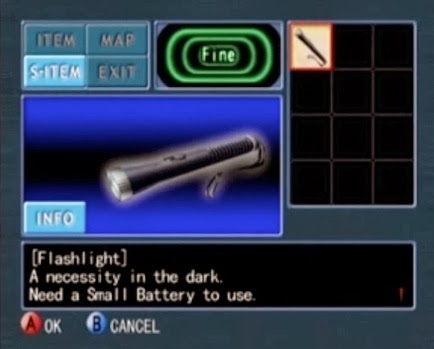

If you have item descriptions, why not make them interesting or useful? Everybody already knew it was a trashcan before they examined it.

It may sound a bit unintuitive, but horror games work surprisingly well without rocket launchers. And you’d be surprised how fun mystery games can be when they don’t have RPG mechanics shoved into them.

Fail in every other category if you must, but do not fail in this: map and menu screens must not require a loading pause to display. It is bad enough that you have to bring these up in the first place. Oh, and checking the map every two steps is not fun.

Follow these tips and you’ll be well on your way to making a horror game that is fresh and original! After which you can make endless sequels!