Mikael Hedberg is not currently working at Frictional Games.

Who am I?

I am Mikael Hedberg and I’m the writer. I write all sorts of text that shows up in the game. I give actors lines to say and then ask them to scream a few times, because their character will most likely die at some point.

Background

I’ve been a gamer for as long as I can remember. I played everything I could get my hands on, board games, RPGs, and of course computer games. I can’t remember a brand or anything, but the very first computer I owned was a green keyboard with rubber keys. It didn’t have any memory to actually save things, so you had to program every game you wanted to play. I had a few sheets of paper filled with code which you painstakingly had to type before you could play. And what riveting games I got to play. Oh, the thrills of guessing that number between 1 and 100 or dodging those falling letters. Those were the days.

I did eventually upgrade to an Amiga which was the first time I encountered real story in games. LucasArts and Sierra titles quickly became my addiction. I liked all of them, but more than any other I would say Gabriel Knight: Sins of the Fathers really made me go, “Oh, these can get pretty dark and tell real stories.”

I was kind of late to the computer RPG party, because playing a lot of tabletop RPGs made me think they were pretty bad in comparison. I did start liking them around the release of Fallout 2 and played a bunch of the RPGs released around that time. I still consider Arcanum: Of Steamworks and Magick Obscura to be one of the best computer games I’ve ever played. You see, the thing about being a tabletop RPG player is that I’ve played and hosted easily over a hundred different stories in this very free and responsive type of play. Going to computer games, it’s really difficult to get excited by the storytelling because it’s rarely that interesting. Not because it doesn’t tell the right stories, but because I never feel like I’m really doing anything. I feel like I’m slowly moving a movie forward. It’s like all I do is power the projector by pushing keys. People often get dumbstruck when I don’t go nuts over games like the Last of Us. They are great at story, they tell me. Yes, they really are, but we have always had good writing and conventional storytelling. Look at the Sierra games from the 90s. They are absolutely fantastic in that respect.

I do get more excited with games that either try to give me that sense of responsibility like the Fallout games or games that try to merge gameplay and story like Heavy Rain. If you mess up, you don’t just fail, you actually fail someone in the game, you change the story. That’s when story matters, that’s when it gets interesting to me.

I’ve always wanted to tell a really good story in a game where it makes you feel like I do when I play tabletop RPGs. A game where you are concerned about what you are doing, not because you might fail some gameplay, but because it may take the story somewhere you don’t want it to go. Where your actions affect the lives of the characters you meet in a meaningful way and their well-being is reflected back on you. Basically to be human, but in another world.

I started out my career at a pretty big company in Stockholm. It was a very educational experience concerning how the business works. However, it was very frustrating trying to get anything done. In the end I felt like I put maybe 5% of my time into the writing and 95% into company politics, talking to people and trying to get everyone on board. The one thing I learned about being a game writer is: You are responsible for the story, but you don’t have mandate to actually control the story. Impossible situation, you say? I thought so, so I kind of ran away to Japan for a while.

One day as I sat there in my house on a snowy peak in Japan there came a knocking on my door. It was Jens, an old friend of mine from school.

“Gotham needs you,” he said.

“What?”

“Sorry, wrong house. Oh, hi Mike. You want to do some writing for Frictional Games?”

“No, man. I’m done with game writing. My life is all about crochet now. Wanna see?”

“Wow, that’s like really bad…”

“Well, I just started.”

“No, I mean, like really really bad…”

“All right, you made your point. I’ll take the writing gig.”

“What is this even supposed to be?!”

“I said I’d do it already!”

That’s how I ended up at Frictional Games. And there’s at least five words of truth to that story.

Home away from home.

What do I do?

Explaining what I do and the amount of control I have over the narrative is very difficult, but I’ll give it try. Unlike what many seem to think I don’t set up the game like a screenwriter would set up a movie. I don’t precede the making of the game like a screenwriter, I write the game while in production. What happens in preproduction is more of setting up what the game will be rather than the story and the plot itself. Thomas, my boss, will explain what he wants thematically and roughly what events he wants the player to experience. It often sounds like story, but it really isn’t, even though it sometimes lends itself to something looking like a narrative. This preproduction talk mostly limits the story through theme and game structure. In the case of the Frictional Games titles I’ve worked on they all go with real-time linear progression of levels with a horror theme. This setup could make a thousand different stories if not more, but it also makes thousands of stories impossible to tell. After preproduction I should have an idea of what the game could be, but also what it absolutely can’t be.

Thomas then starts designing levels, providing a procedural journey through the levels with some suggestions for story content that could or sometime absolutely should be included. When I get to do the real work, actually writing the text you read or the dialog you hear in game, all the people in the company are already doing their thing, working from the level design. So, when I start writing there is already a level in production, gameplay designed, and a good sense of what the player will be doing. To make this work I can’t just start writing what I think would make a good story, but rather what would make the game work – and if there’s enough room, try to make it interesting beyond just being functional.

Step one in my work is always to have whatever the player is doing make some sense. Before I can get into shaping interesting characters or explain the plot, I need to hit that mark.

Take one of the very first puzzles in Amnesia. The door is covered in fleshy goo (the Shadow). The player is to create a concoction to dissolve it to continue.

The door itself and the goo in front of it takes care of itself. The player understands that this is not like other doors and something needs to be done to proceed. The first step is to introduce the solution, the recipe to dissolve the goo. Now this is pretty strange for someone to have lying around, so it needs to be justified somehow. I could start with saying Alexander’s plumbing is clogging up and that he purposefully created the recipe. Problem solved. Now that it is justified, I look at it. Can it be improved? Can I say something else about the world and the characters within it?

“This is my third attempt to produce artificial Vitae. The former compounds lacked the potency I need, but I sense I’m close. Calamine and Orpiment are a given and the Cuprite binds them well. This time I will attempt Aqua Regia instead of Aqua Fortis in hope it will produce a more even solution.The experiment was unsuccessful. The solution is highly acidic and proves impractical to put to any use except as a detergent. Organic tissue reacts especially violently to the solution and should be handled with the greatest care. I might be able to use the recipe, but I’m losing hope that I will find an alchemic solution to my predicament.”

Yes. Let’s make it one of Alexander’s experiments to create the vitae he wants so badly, but a failed one that has the effect the player wants. Now suddenly the note justifying the puzzle just told us about Alexander and further detailed his journey. Also the kind of throw away attitude Alexander has towards the concoction gives the player a sense of “Even though Alexander didn’t, I can put that to use”. It’s not just Daniel blindly following Alexander’s footsteps. Daniel actually finds a use to something that Alexander didn’t, which creates a nice distance between the two characters. So what started as a strictly functional solution ends up helping me talk about these two characters and enrich the story and reveal Alexander’s motives.

Justification followed by building story is the foundation of my work.

Pretty early on I know what I want the overall story to be and I map out what I need to tell that story in my head. To accommodate for changes and things that others, mostly Thomas want to include, I need to keep this plan pretty flexible. I try to keep this in mind when writing early texts as well, so I don’t paint myself into a corner. The further we get into the game, the more I dare to nail things down as the rest of the team has subconsciously started to take this as the obviously best version of the narrative.

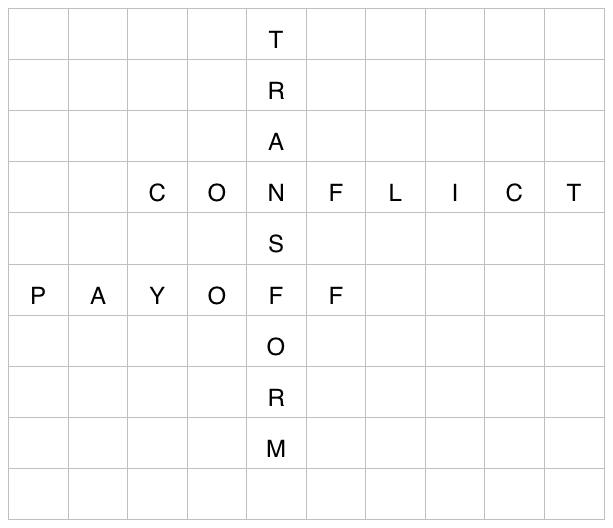

Illustration time! Let’s say I have three pieces of information I need to get into the game so the story works the way I want it to. Let’s call them Transform, Conflict, and Payoff.

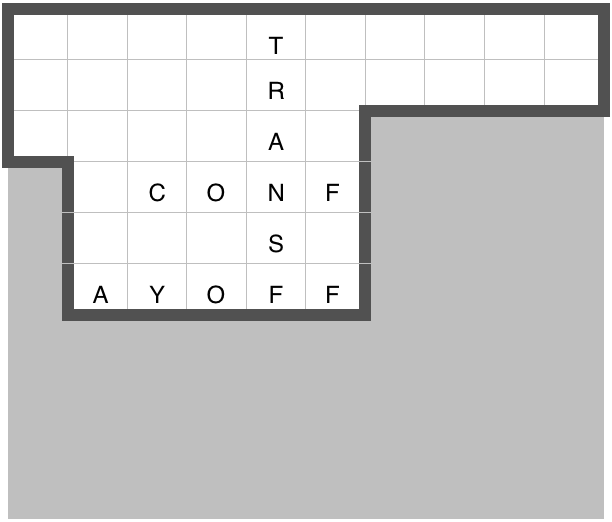

And then we put the game and its structure on top of that:

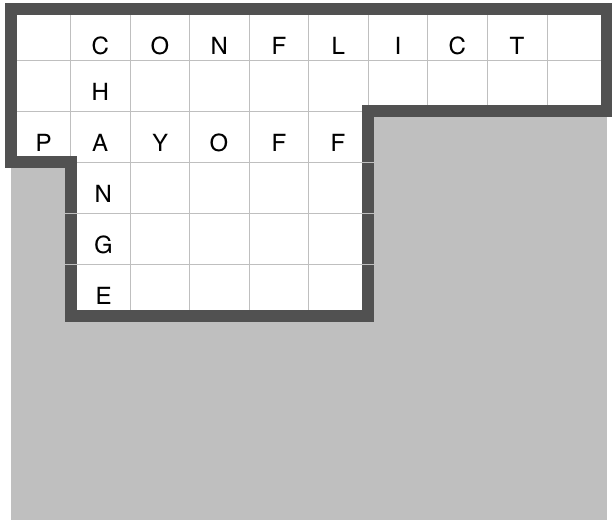

Then we make the best of the situation:

“— Mike, we cut another level.”

“Muddafu—!”

Maybe not the best of illustrations, but it’s sort of what I do. I try keep an idea of the overall information I need to put into the game to tell the story I’m aiming for, and then keep it flexible enough so I can tell that story in a range of different ways. It’s not that I come up with thousands of versions, but instead remain opportunistic enough to fit the information I need where ever it will fit.

What’s probably most surprising to people is that I don’t get to boss people around and claim that the story demands this or that. Many would probably equate this to the story taking a backseat and is more of an afterthought, but that would be missing the point about the process. Yes, I don’t get to plan and direct the story, but I kind of get to cultivate it. Over time shaping a nice little bonsai tree out of the chaos that feeds it. And since we started on SOMA, Thomas has started to show more interest in storytelling which takes a much more transformative form as he has the power to actually tell the team to rework things. Thomas and I more openly discuss where we think the story should go this time around and what we would both like to see, so it’s easier getting a good framework down to work from. Funnily enough, I consider Thomas my most powerful ally as well as the most destructive force on the team, since he could suddenly decide to reshape a level to make it fit the narrative better or on the other hand decide to cut a critical scene due to gameplay flow. Ultimately I need to trust him to make the game he wants. Because if I cultivate a little story bonsai tree, I’m sure Thomas is worried about a whole garden of different fauna, like graphical coherency, technical efficiency and engaging gameplay.

As always I just need to roll with the punches.