Before starting Until Dawn my hopes for the game weren’t very high. I thought it was going to be a half-baked and campy interactive movie filled with unlikable characters and cheap jump scares. However, it turned out a lot better than I could have imagined and it now stands as one of my favorite horror games ever. Sure, the game can get really campy at times, and it has its fair share of jump scares. But it also features a clever script, an excellent setting, amazing atmosphere and (to my surprise) also managed to be extremely tense and scary at times.

The game knows that it is a B-movie horror, but it takes that at heart and instead of hiding behind satire it’s determined to be the best B-movie possible. This works a lot better than I’d expected it to and the result is an engaging ride that channels other (in my opinion) great B-horror like The Descent, Saw, Dog Soldiers and Evil Dead. It takes itself just seriously enough for you to overlook the sillier aspects yet still feel emotionally invested in the fates of the characters.

Until Dawn is not without its faults of course, but it does a lot of things incredibly well. I have grown quite tired of the interactive movie format over the years. Playing through over three seasons of Telltale games have made the experience feel samey, and I am always frustrated with how little I get to actually play, explore and shape the narrative. Until Dawn far from reinvents the interactive movie genre, in fact it’s fascinating how alike all of these games are, but it changes just enough to make the experience feel fresh again. This is where I think things get really interesting, because while the changes aren’t anything major, they have a huge impact on the end experience.

Now it’s time to take a closer look at the inner workings of Until Dawn, and to do so we have to enter spoiler territory. I will try to stay away from larger reveals, but it will still be enough to ruin a lot of the fun. Until Dawn relies a lot on uncertainty, so if you haven’t played the game (which I really recommend you do) and want the best possible experience, go and play it before reading more of this essay.

With that disclaimer out of the way, let’s start with the things that Until Dawn does really well:

Multiple Deaths System

First up is the most prominent and possibly the most effective feature of the game: any character can die at any time. Well, to be fair, in practice they can’t – but it sure feels like it. Some characters can be killed pretty early on in the story while some can’t die until the very end. The trick is that the first time you play it you can never be sure. Whenever things start to get dangerous for a character you always feel that there’s a chance that a bad choice or a missed quick time event can lead to their death. And since Until Dawn saves after every important choice, there is no going back. Any death is basically permanent.

Heavy Rain did a similar thing a couple of years back, but Until Dawn takes it to next level. The main reason for this is that death feels like a possibility from almost the start through to the bitter end. In Heavy Rain the scenes that feel like life-or-death-moments are pretty spread out, but in Until Dawn they permeate the entire experience. Early on in the game, most of these turn out to be the characters playing pranks on one another, but because of how it all is setup you can never be sure.

The game also helps to build up this tension by very explicitly telling the player what’s at stake. It also uses a lot of filmic tricks, such as showing us, through the eyes of the monster, how the characters are being stalked. Normally I don’t like this sort of thing in games as it lessens the feel of it being “my story”, but here it works really well. It points out that the characters are now in danger, and together with the game’s initial warnings, it makes it very clear that you have to be on alert.

The final aspect that I think makes this work so much better here than in Heavy Rain is that Until Dawn is a proper horror game. The tension and uncertainty built from knowing that any character might perish goes hand-in-hand with the the game’s thick atmosphere. Both of these constantly reinforce one another and do a great job of making you feel vulnerable and under constant threat. A great way to test this is to simply replay the game. Once you know a certain section poses no actual danger for a character, much of the tension dissipates and the scene goes from scary to feeling tame. It’s like turning off the music in a horror movie – without all necessary elements in place the effect is lost.

This system is not only a way of making the game scary, it’s also a great way of keeping the narrative going. There’s almost never any chance of getting stuck and thereby having to repeat the same section over and over. This makes sure that frustration is kept to a minimum, letting players be focused on becoming immersed in the narrative. If players become stuck trying figure out how to progress, immersion is quickly decreased, and lot of the horror along with it.

By not having a game over screen, you also get rid of the feeling of having seen the worst the game has to offer. In Until Dawn it is almost the opposite; once you have seen a character meet a horrible death, you know anyone can be next. Normally the death scene is a relief for the player, but here it raises the stakes instead.

Finally, by letting it be possible for every character to die, you earn your outcome in a way that you usually don’t do in interactive movies. Normally, because branches tend to quickly collapse, your choices are more about pondering the decision, and less about the outcome. But in Until Dawn, your choice will determine who lives and dies, which gives you a much more palpable feel to your decisions.

It is pretty clear that this kind of system is close to optimal for a horror game. So why doesn’t every horror game use it? The most obvious answer is that not every game is able to support a large cast of playable (and killable) characters, but there’s another reason that’s much more difficult to get around. In a fully playable game, the number of places where the player can die skyrockets, and it becomes really hard to make sure that each one is satisfactory from a narrative perspective.

Until Dawn gets around this by relying a lot on “successful failures”. For instance, if you fail at a quick time event when a character jumps across a chasm, the game can show a clip of the character fumbling and just barely making it across. So you get feedback for failing the challenge, but your character didn’t die and the narrative can continue along the same path. In a fully playable game, this is simply not possible. If the player fails at a jump the mechanics says they will fall down. It isn’t possible to give the player any help (e.g. a push in the right direction) to make sure they complete it, either. There are simply too many ways to perform an action, and besides it would quickly become glaringly obvious. This means that not only does a fully playable game have to deal with many more possible deaths, it’s also a lot less predictable how they will unfold.

Side note: I wrote about this as a potential death system over six years ago. One of my suggestions was to have a Cube-like setup, which is pretty much exactly what Until Dawn does, and it worked much better than I’d expected it to.

Ability To Plan

The ability to make plans is part of what it means to be human, and there are good reasons to think it’s one of the biggest reasons for us developing a consciousness (more info here). When we plan we get to flex our most advanced mental muscle: the ability to simulate future outcomes. Thus allowing us to make plans is an vital part of human expression.

Most games allow planning in some form. And not just any sort of planning, but meaningful planning where you can weigh your current data, plot a future course of actions, execute on those actions and then feel like you get a measurable outcome in the end. In Super Mario Bros you need to plan what path to take and how to avoid upcoming obstacles. In an RPG you need to consider how you spend your money and experience points to build up your character to suit your style of play and that character’s effectiveness. There are tons of examples like this in games, and most games feature it in one form or another. Allowing for good planning is a one of the core features that make a game feel engaging.

However, in interactive movies, it’s all about reacting to the events that unfold. There’s not really any planning involved. You sort of live in the moment, and don’t have much say in what happens next. For most of the time, the playable characters do what they feel like and let you occasionally take control to react to dangerous events or to make a tough decision for them. Sure, sometimes you can makes up plans to support certain characters so that they’ll side with you later on. But all of that is pretty fuzzy, and mostly it won’t be very useful to you. It is often hard to get a sense of what you near future possibilities will be at all. You might plan to do A, B and then C, only to have the game take control after action A and do something completely different. This means that, for the most part, it’s impossible to plan ahead; in fact if you plan too much you will most likely be disappointed. It is often best to just go along with the flow. I think this lack of an ability to plan is one of the key reasons why many people feel that interactive movies are not proper games.

Side note: I think that the inability to plan and over reliance on reactive play is also why many people feel walking simulators aren’t proper games. It is often stated that it depends on fail-states and the like, but I do not think that holds up. I will get back to this a bit more at the end of this essay.

Until Dawn shares the basics of this problem too, but because of the way certain things are designed it’s possible to do a certain level of planning. This is something that I can’t recall seeing in another interactive movie style of game, and it made the experience a lot more engaging to me.

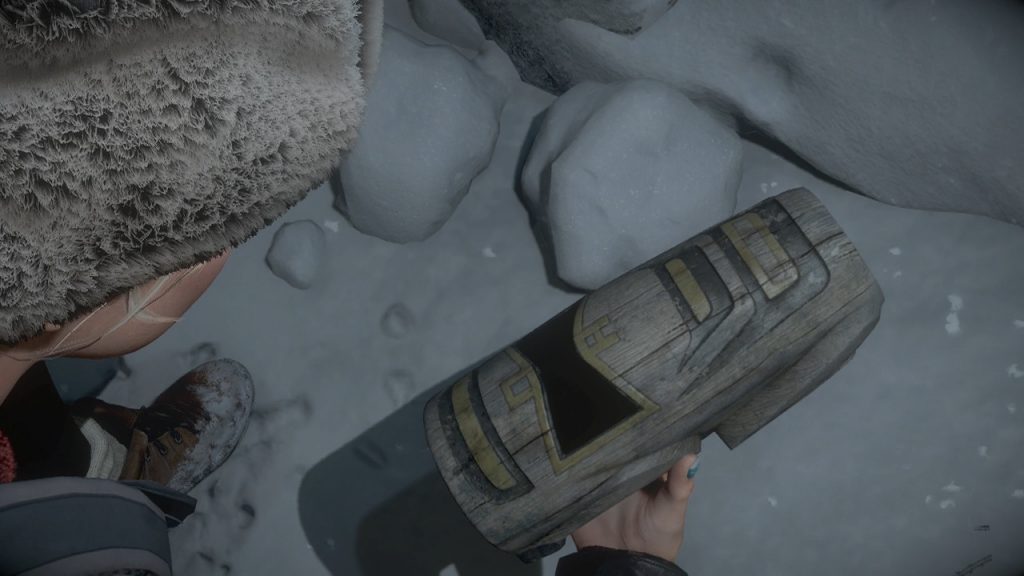

The first thing that allows this are the totems. These are items that when picked up give you a brief glimpse of a possible future happening. Sometimes they show you how a character dies and sometimes they give you hints on important choices to make. For instance, in one totem you see that giving a certain character a flare gun gave you a good outcome. Now you know that you need to find a flare gun somewhere and make sure that a specific character gets it. It’s not much, but what it does is that it forces you to guess how scenes might unfold, and you try to match up the current events with the totem visions you have seen. This forecasting gives the game a certain sense of strategy and forces you to consider current events more carefully. It’s not a major game changer, but it’s enough to give that extra sense of engagement.

What I found to be even more effective in allowing me to plan was in guessing plot-points which became a crucial part of the decision making. The most prominent of these was figuring out who was behind the torment of the other characters. I theorized quite early on who it was, and could then make a bunch of choices based around that. Connected to this is the fact that this is probably the only game I have played where it turned out to be beneficial to be a skeptic. I suspected that the movements of a spirit board was due to someone messing with it, which (together with a couple of other pieces of evidence) then led me to believe that certain ghost appearances couldn’t be real either. All of these conclusions turned out to be true and allowed me to make much better decisions. In the end, the whole revelation is a bit implausible and very Scooby Doo-like. But it went quite nicely with the B-horror tone of the story and more than any other interactive movie I’ve played it made me feel that my understanding of the story mattered.

This doesn’t mean that Until Dawn does planning perfectly – far from it. But it does show that smaller design changes can make a world of difference. It’s also very important to note that a big reason why all this works is because of the Multiple Deaths System. Without having the very clear feedback of seeing your characters die or survive, and the tension that comes along with that, the features I’ve mentioned would have lost a lot of their impact.

Other Good Stuff

Those previous two points are what I feel are the major elements that make Until Dawn stand out from the crowd. But the good stuff doesn’t end there. There are a lot of other interesting design choices that have a big influence on the experience.

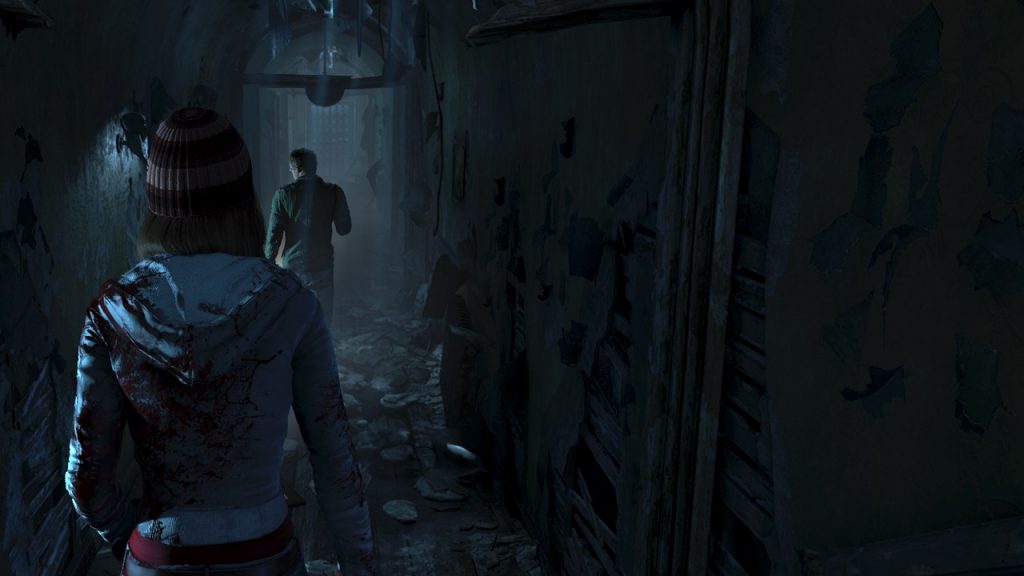

First, exploration bits feels much better than in other interactive movie games. Often when you’re given control over your character, the pacing often gets messed up. But in Until Dawn it just makes the game feel more like Resident Evil without the combat. One contributing factor is that that there’re a lot of clues and totems for the player to find. These provide a nice sense of the sort of “item looting” common in survival horror games, and since all the things you can find are a part of the narrative, it never feels out of place either. The other factor is that you never know when you’ll encounter danger, so walking down a murky hallway can be incredibly tense. Combined, these two elements make these exploration segments very engaging and make them feel part of the overall narrative.

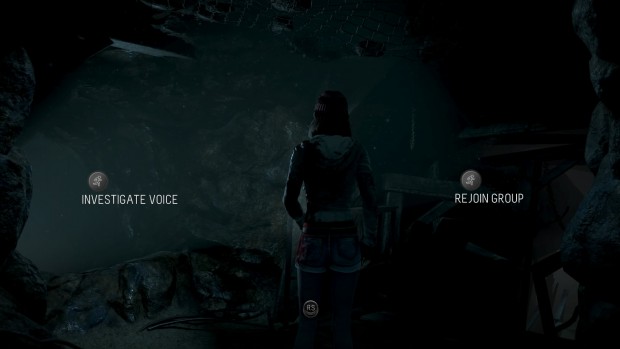

Second, knowledge of the game’s lore can help you survive situations, meaning that you’re rewarded for paying more attention to it. For instance, there’s one moment where knowing that monsters can’t see you if you stand still is crucial when making a choice. And in another, remembering that monsters can imitate the voices of their prey will help you avoid walking into a trap.

Third, each of the characters has meters that go up and down as you make choices. At first it feels like unnecessary fluff, but it actually helps you get a bit more “ownership” over the characters. It’s sort of an extension of the “Clementine will remember this”-line from the Walking Dead, giving an indicator that your actions have consequences. But more than that I think it’s a way to see that your character changes depending on how you play. And then, the effect is similar to how you get more attached to your character in X-COM as they level up.

Fourth, it constantly varies its environments. This is what I like to call the Super Mario way of location progression. It has long been a common thing in games to let the player linearly progress through various environments. You start up in the forest, then go to the swamps, then to the mountains and finally you arrive at the castle. Super Mario doesn’t work like that. Instead it constantly swaps between the environments, keeping the locations fresh. I think this is a really good design principle that far too few games use. Until Dawn does it well, both by having a lot of different locations near each other, and by switching character perspectives throughout the experience. This means that normally kind-of-dull environments, like the mines, always feel fresh and interesting to be in.

Again it’s important to note here how much the Multiple Death system plays into all of these things. For instance, much of the dread that makes the exploration and clue hunting engaging comes from the knowledge that any choice could be a crucial one. The same is true for the second and third points too. And the varied environments rely heavily on there being multiple characters to play.

The Not So Good Stuff

Now that I have gone over the good things, it’s time to briefly cover some of the not-so-good things in Until Dawn.

- The game often doesn’t support a bunch of actions that it should have been possible to perform. For instance, there are doors here and there that it should have been possible to at least try to open. And far worse, at one point the characters turn away from a gate they could easily have jumped over. (You climb far more difficult things throughout the game).

- A few of the choices in the game can lead to unfair dead-ends. For instance, one character is bound to die pretty early on if you haven’t made a few specific choices earlier in the game. The big problem here is not that it felt a bit unfair, but that you can’t see any reason why it happens. If you can just get a sense of what went wrong, you can learn from your mistakes and do better later. But when that’s not possible, your sense of being able to plan is decreased, which is a shame when the game builds that up so nicely in other places.

- The settings in Until Dawn look great, but I always felt that I was unable to properly explore them. One reason for this was the locked camera angles which focus more on making the shot look nice than on providing a good play space. Another reason is that many set pieces are simply not possible to explore. The game just decides that the characters wants to do something else instead and has them leave the area. The game is excellent at building mood in many ways, but I felt annoyed at how the game seemed to constantly hinder me from taking it all in properly.

- It is very uncertain when the control over your character will end. The best is when a dangerous encounter happens or you reach another character. In these cases the control method switch (from full analog to quick time events or dialog) and the break in control feels natural. But on many occasions the game starts a cutscene when you don’t expect it to. For instance, after going down some stairs, the game suddenly decides that your character should go into a home cinema room despite there being lots of other places to explore. From a design point of view I can understand why this happens – you need to make sure that certain plot events trigger properly. But as a player these things deprive me of my agency and some of the immersion is lost.

There are a few more of these things, and what they all have in common is that they are typical of, or even sometimes inherent to, the format of interactive movies. I really liked Until Dawn, but I can’t help feeling unsatisfied by this style of games. Despite having gone over all the the things that Until Dawn does right, it still feels like there’s something fundamental missing to it all. Most of the story is told through cutscenes, and for much of the game you are more of an observer than an active participant. I want interactive stories that I can play from start to end, not just a little now-and-then.

Interactive Movies And Beyond

I feel I have a weird relationship with interactive movies. As I mentioned earlier, after playing through a bunch of Telltale games I’ve grown a bit bit tired of the format. But despite that they keep pulling me back. I ended up liking Until Dawn a lot more than I expected. Shortly after I also gave Life Is Strange a go and while it wasn’t as good as Until Dawn, I liked it quite a bit too.

So why do I like them? I think there are three major reasons:

- They have a proper setup that defines who you are and why you are there. I am so sick of games, and it’s especially common among horror games, that just throw me into an environment and expect me to care without giving me a reason to do so. Interactive movies (well most of them at least) work hard to provide intrigue and mystery from the get-go, properly setting me up to enjoy the rest of the story.

- The main focus is on telling a story. I don’t mean this just by them being very linear and movie-like, but more that just about every choice is made in accordance to intended narrative. For instance, Until Dawn has collectibles but puts a lot of effort into making sure that they are connected to story. This creates worlds that feel more “real” and are easier to become lost in.

- They lack the fluff that that is so common in other games. The uninspired shoot-out sections that are obviously just there to make the game longer, extensive weapon upgrading, narrative-wise meaningless collectibles, filler mini-games and so forth. Interactive movies aim at giving you a specific experience and make sure that all of the game’s aspects help fulfill that goal.

When other much more gameplay-focused games try to do storytelling it often just gets in the way. I always get annoyed by action games that start with overly long expositions, and just want them to get to the point. In fact, in other games it feels like the more overt storytelling actually gets in the way of the narrative the game is “supposed” to be telling.

It might seem like I’m heading towards the good old “gameplay vs story” discussion here, but the point I’m getting at is a bit different. I don’t think that gameplay is something inherently opposite of story. In fact, in the way I see story many of the classically super-gameplay-focused games like Super Mario have a ton of story in them. As you board an airship dodging cannonballs while trying to get one of Bowser’s sons, a very rich narrative is created.

Instead, the problem lies in controlling the player’s mental model of the game. That is how they perceive the game’s virtual world to work, and what aspects that become most important in shaping how decisions are made and emotions evoked. When you want to focus on story you have to cut back on a lot of useful gameplay methods. The biggest issue is that you need to make sure that players do not end up optimizing for best possible progression, but act according to the intended narrative. There are also a bunch of things to consider in order to keep players immersed in the world. (For more information check out this essay). In the end it all comes down to storytelling games getting less gameplay per buck, as you can’t rely on a fun and addictive gameplay system being core of the experience.

We found this out when creating SOMA. It’s the one of our games that has got the most praise for its story, but it’s also perceived as the one lacking the most in the gameplay department. Recently it occurred to me that one of the major things that make people feel the game lacks gameplay is because most choices are made as reactions. This even includes many of the puzzles, which have been designed with the focus to be streamlined and coherent with the narrative. This makes the game lack that proper feeling of being able to meaningfully plan ahead. So despite there being lots of things to do in SOMA, it feels like something is missing gameplay-wise.

The problem here is that we simply cannot increase the gameplay in any trivial manner. That would cause a whole bunch of other, worse, issues. So the way forward is to find other ways in which to increase the sense of “playability”. And here I think there are at least two vital things that can be learned from Until Dawn:

- To find ways to, in a story-focused fashion, ramp up the tension and sense of accomplishment. The Multiple Deaths System in Until Dawn does a fantastic job at this.

- To allow players to make plans based upon how the narrative unfolds. The player should not just react to events as they occur but be able use tactics and long term planning in a way that feels meaningful.

How to do this in a gameplay-focused experience is far from straightforward. You can’t just make a game with multiple characters and call it a day; most likely the effect of the Multiple Deaths System will need to work in a quite different manner. But what I find encouraging is that if we simply focus on increasing the ability to plan, it will allow us to view the problem from different, and probably much more fruitful angles. I feel there is something very much worth exploring here, and it will be interesting to see what can come out of it.