Who am I?

Hello! I’m Aaron Clifford, one of the artists here at Frictional Games. Right now there are four of us artists and I’m relatively new around here. I started collaborating with Frictional back in April 2012 as a contractor, making props and other smaller bits for SOMA. A few months later I was brought on to the team full-time and, as they say, the rest is history.

Since we all work remotely, I do my stuff from my home in a suburb of London, England. I was the only one representing the British in Frictional for a while, but now we have a few! You’ll get to see their blog posts and learn about them soon, I’m sure.

Background

Like any kid back in the 90s I had the pipe dream of one day growing up and making video games. I guess I just clung on to that dream a little longer than some of the others. Games in one form or another have always been with me; I think the first time I got my little hands on a video game must have been on the Amiga 500. I have very vivid memories of California Games, Prince of Persia and a pretty obscure game called It Came from the Desert. I was stuck with that machine and a Sega Master System (for which I only had a couple of games, including the built-in Alex the Kid) long after those became redundant until I was given £100 after my family sold our house. I blew it all on buying a Sega Megadrive/Genesis, only to have it stolen by the people working on our new house. They actually replaced the console inside the box with a couple of bricks!

Fast-forward past a few years of crying and I finally got my Megadrive (which I never let out of my sight), Playstation and eventually a PC which is when I started digging into the inner workings of games.

Inspired by old Sierra games I always wanted to make a point & click adventure. I remember scrawling countless pages of story and scribbling level plans for the game I wanted to make. I can’t really remember what it was, but it was something along the lines of a Broken Sword & Resident Evil amalgamation.

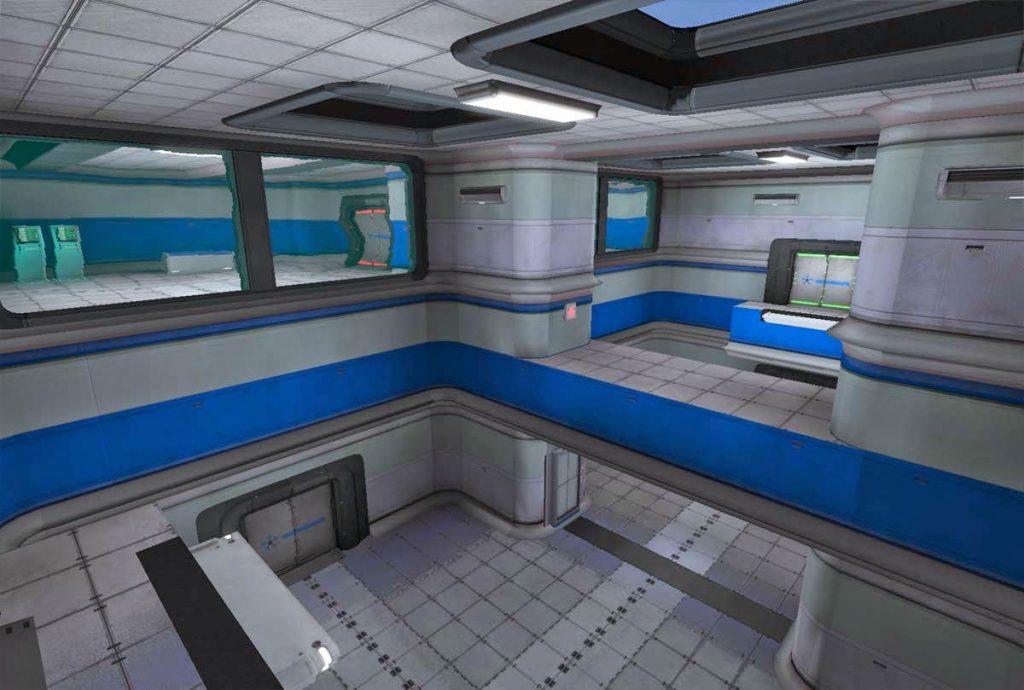

Then Half-Life and Counterstrike were released along with their mod tools and I started playing with the Hammer editor, making maps for CS which me and a few friends would play around in, stuff like “jump maps” (remember those?) and grenade dodgeball arenas. This was when I decided that, in my pipe dream of becoming a game developer, I’d take the path of a level artist. Having people run around inside my creations and enjoying themselves really gave me a lot of satisfaction.

So after high school I signed up for a college course that centered on computer games, digital art and media. Unfortunately it left a lot to be desired – I came away with just a few basic Photoshop and Flash skills. Undeterred and determined to make it into the industry I took it upon myself to learn the tools of the trade. I grabbed some free 3D programs like Milkshape and Blender and I started making guns, cars, space ships & crates (as is usual for a new 3D artist!) and eventually established myself in the modding community, helping out on various overly ambitious projects that eventually collapsed, but nonetheless making a lot of friends who would become professionals in the industry. A few are still good friends to this day.

Like a few of us at this company I never landed a big job in a proper studio, instead I lent my skills to various projects as a freelancer, making enough money to get by. I did that for a couple of years but the unstable nature of freelancing didn’t really appeal to me. I applied to a few off-site fulltime jobs and some studios in London – due to family stuff I couldn’t really move out of London at the time – but finding a job in games around here is surprisingly tough. I struck it lucky when applying to a job posting at Frictional Games. I remember seeing the Penumbra tech demo and really digging it; Amnesia had just blown up and first-person horror was the order of the day. What Frictional was doing at the time was really quite unique and interesting to me so I was happy to see in the job description that people here work remotely which suited my situation perfectly.

I was always happiest working long-term with a team on a project we all care about. Frictional Games is really fulfilling for me in that respect, it’s like being back working on a project with friends only now I get paid and we actually release things.

What do I do?

An artist at Frictional has to wear many hats. This is something I’ve always been used to, and when friends tell me all they do is make textures all day or work on vehicles, I can never get my head around that. We generally work on whatever graphics that need creating for the project.

Every artist is usually responsible for a level each. We will pair up with a scripter and work on a level for 4-8 weeks bringing it from an empty space into a level in which the player can run around in, interact and advance the story. This doesn’t mean the work is done on the level at the end of our scheduled time on it, it just means by the time the weeks you have on it are up, there should be a decent amount of atmosphere to portray the mood of the level and you should be able to play through it from start to finish with all of the major events and activities in the design document present. At a later date I (or another artist) will come back to it to either change/rework it due to a design decision or if the design is solid, just work on the visuals more and bring it up to a better standard.

The number of tools I use has gone down a lot over the years and as software has improved. Day-to-day I use Modo for all my 3D polygon-pushing needs, Photoshop for my texture painting and HPL3’s toolset for everything game related.

Allow me to take you on a quick journey through the creation of a game asset from idea to game.

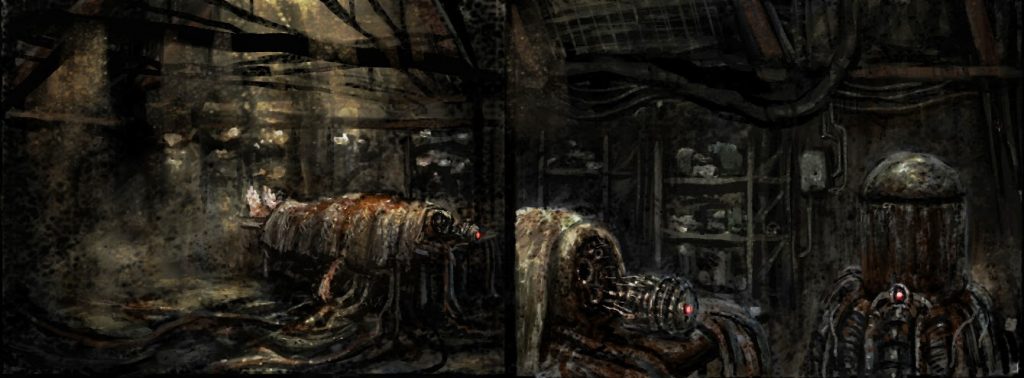

It usually starts with having a sketch kindly provided by Rasmus Gunnarsson or David Satzinger, two of our artists who are gifted in the traditional arts and visualisation. Not always, however, a lot of the time we just need to use our own imaginations and come up with designs for things on-the-fly.

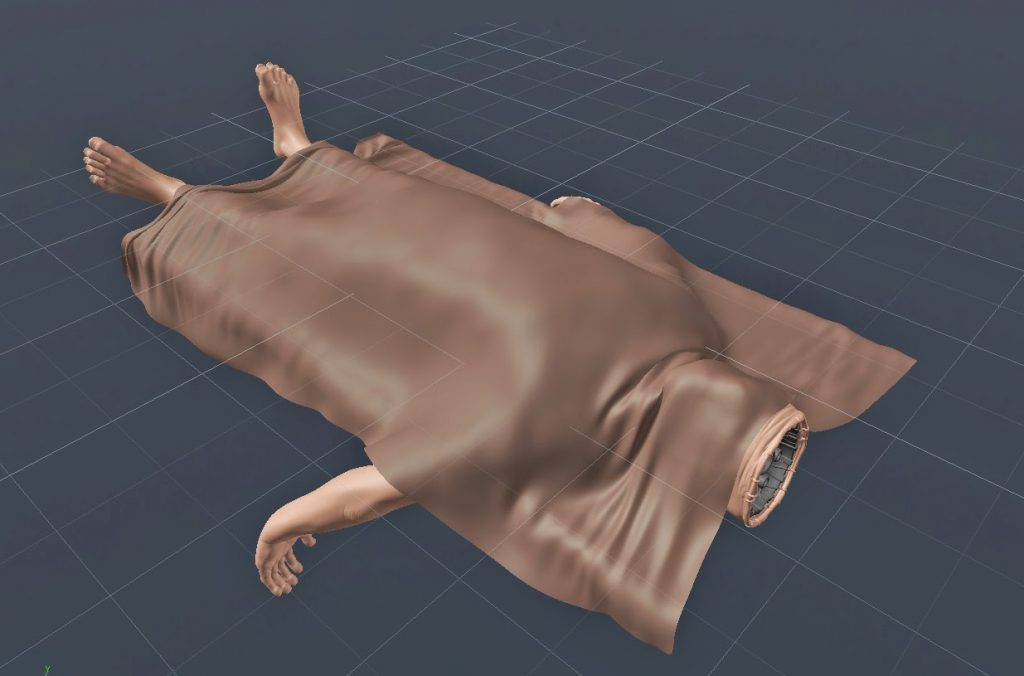

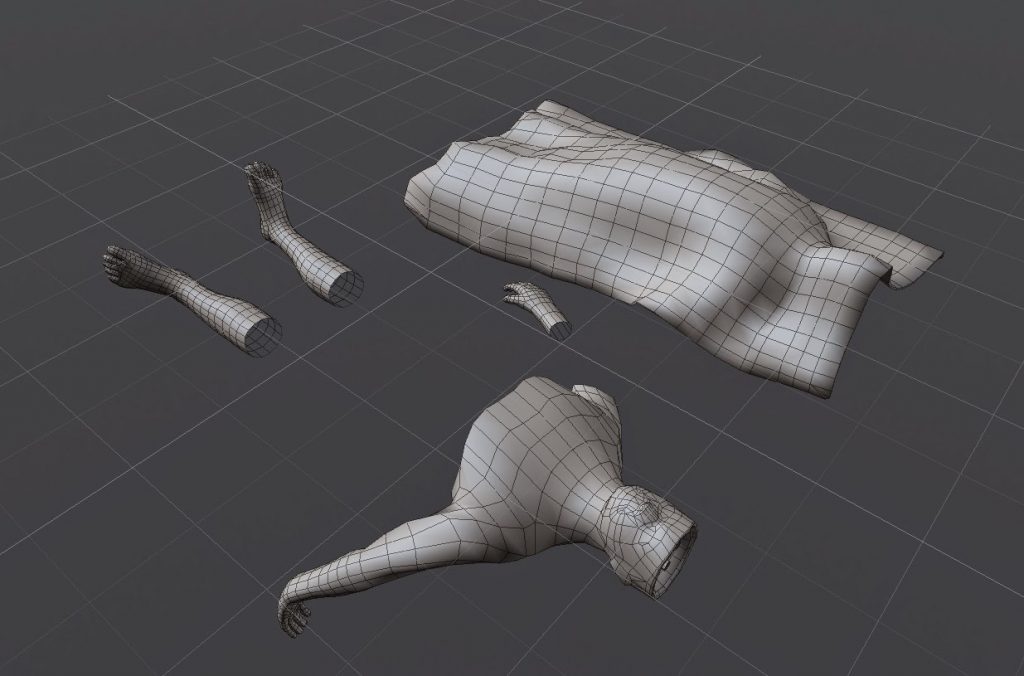

I usually start by making a high resolution mesh of the object. There are no limits on polygon counts here, this mesh is made up of millions and will be used to “bake” down detail to the lower-resolution in-game mesh.

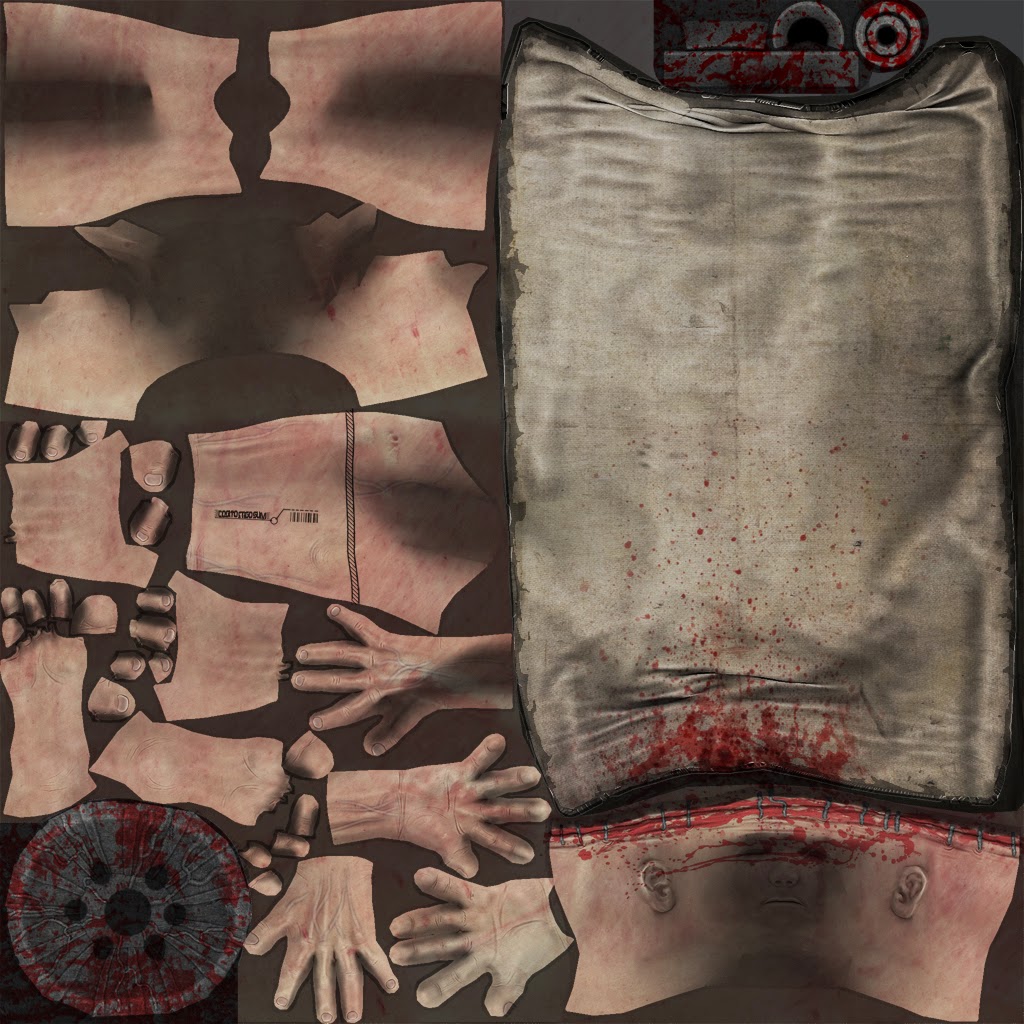

Then I make the low polygon mesh. This will be the one that displays in game, so the polygon count is a factor here. The main objective is to have a silhouette that’s as smooth as possible so curves don’t look choppy or faceted. Polygons have been saved by not modelling the torso or any face details, as they will be covered up by the sheet in game. Every little helps!

Now I’ll “UV Map” the model, which is the process of basically unfolding the mesh into a 2D representation – like reverse-engineering a cardboard box and flattening it all out. That UV Map is then painted over in Photoshop to give it color, texture and make it look real.

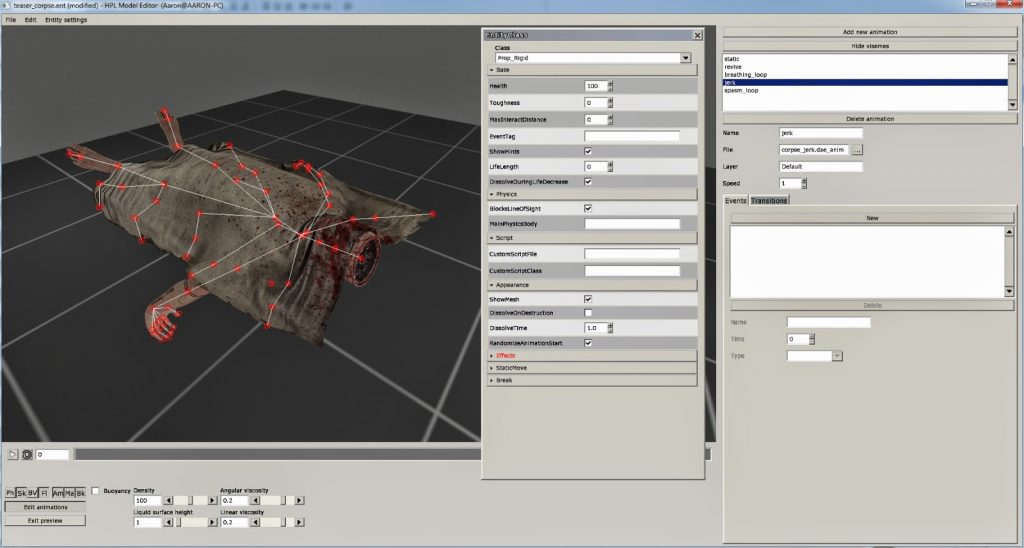

In this case, as seen in our debut gameplay trailer, our Raznik is going to thrash around, so he’ll need animation. He’s given a skeleton and handed over to one of our talented outsourcers for animating. Mikael Persson brought Raznik to life in the trailer.

The model is then brought into the HPL Model Editor for setup. This includes adding collision so the player can’t walk through it, adding any animations for triggering in script, attaching lights, effects or sounds – whatever’s needed for the type of asset you’re creating.

The model is now placed into the game world by using the HPL Level Editor. This is pretty much the end of the line for the artist. It is now the scripter’s responsibility to make Raznik squirm and scream in pain when the player pokes around with him. Without the scripter’s input, he would just lie there motionless and that’s not very scary at all…

The finished product as seen in our debut gameplay trailer.

I hope this was an interesting insight into who I am and what an artist does at Frictional Games. If you have any more questions, drop me a line in the comments and I’ll be happy to answer them.

Thanks for reading!