After a little break with updates on the rendering system, holidays and super secret stuff, I could finally get back to terrain rendering this week. This meant work on the final big part of the terrain system: Undergrowth. This is basically grass and any kind of small vegetation close to the ground.

As always, I started out doing a ton of research on the subject to at least have a chance of making proper decisions at the start. The problem with undergrowth/grass is that while I could find a lot of resources, most were quite specific, describing techniques that only worked in special cases. This is quite common when doing technical stuff for games; while there are a lot of nice information, only a very small part is usable in an actual game. This is especially true when dealing with any larger system (like terrain) and not just some localized special effect. In these cases reports from other developers are by far best, and writing these blog posts is partly a way to pay back what I have learned from other people’s work.

Now on with the tech stuff!

Plant Placement Data

The first problem I was faced with was how to define where the undergrowth should be. In all of the resources I found, there was some kind of density texture used (meaning a 2D image where each pixel defines the amount of plants at that point). I did not like this idea very much though, mainly because I would be forced to have lots of textures, one for each undergrowth type, or to not allow overlapping plants (meaning the same area on the map would not be able to contain two different types of undergrowth). There are ways past this (e.g. the FrostBite engine uses sort of texture atlases), but then making it work inside the editor would be a pain, most likely demanding pre-processing and a special editor renderer. I had to do something else.

What I settled on was to use area primitives, simple geometrical shapes that defined where the undergrowth would be. The way this works is that each primitive define a 2D area were plants should be placed. It then also contains variables such as density, allowing one to place thick grass at one place, and a sparser area elsewhere.

I ended up implemented circle and convex polygons primitives for this, which during tests seem to work just fine.

Generating the Plants

The next problem was how generate the actual geometry. My first idea was to simply draw the grass for each area, but there were some problems with this. One major was that it would not look good with overlapping areas. If areas of the same density overlapped, the cross section would have twice the density of the combined area. This did not seem right to me. Also, it was problematic to get a nice distribution only using areas and I was unsure how to save the data.

Once again, the report on the FrostBite engine gave me an idea on how to approach this. They way they did this was to fill a grid a with probability values. For each grid point a random number between 0 and 1 is generated and then compared to to the one saved in the grid. If the generated number is lower than the saved, a plant is generated at that point, else not. Each plant is then offset by random amount, creating a nice uniform but random distribution of the plants!

This system fit perfect with the undergrowth areas and simplified it too. Using this approach, an undergrowth area does not need to worry about generating the actual plants, but only to generate numbers on the grid.

The final version works like this:

There is an undergrowth material for each type of plant that is used on a level. This material specifies the max density of each plant and thus determines how the grid should look. A material with a high density will have a grid with many points and one with a low density will have few grid points. Each point (not all of course, some culling is used) on the grid is checked against a area primitive and a value is calculated. This is then repeated for each area, adding contributions from all areas that cover the same grid point.

This solves the problem of overlapping areas, as the density can never become larger than max defined by the grid. It allows makes it possible to have negative areas, that reduce the amount of undergrowth in a certain place. This way, the two simple area primitives I have implemented can be used for just about any kind of undergrowth layout.

Cache system

Now it is time to discuss how to generate the actual plants. A way to do this is to just generate the geometry for the entire map, but that would take up way too much memory and be quite slow. Instead, I use a cache system that only generate grass close to the camera (this is also how FrostBite does it).

The engine divides the entire terrain into a grid of quads, and then generates cache data for each quad that is close enough to the camera. For each quad, it is checked what areas intersect with it, and layers are made for each undergrowth material that it contain. Then for each layer, plants are generated based on the method described above. The undergrowth material also contains texture and model data as well as a bunch of other properties. For example, the size can be randomized and different parts of the texture used, all to add some variety to the patch of undergrowth. Finally plant is also offset in height according to the heightmap.

This cache generation took quite some work to get good enough. I had problems with the game stuttering as you traveled through a level, and had to do various tricks to make it faster. I also made sure that no more than one patch is generated at each frame (unless the camera is teleported or similar).

Rendering

Once the cache system was in place, rendering the plants were not that much of a problem. Each generated patch comes with the grass in world coordinates, so it is as simple as it can get. The only fancy stuff happening is that grass in the distance is dissolved. This means that the grass does not end with a sharp border, but smoothly fades out.

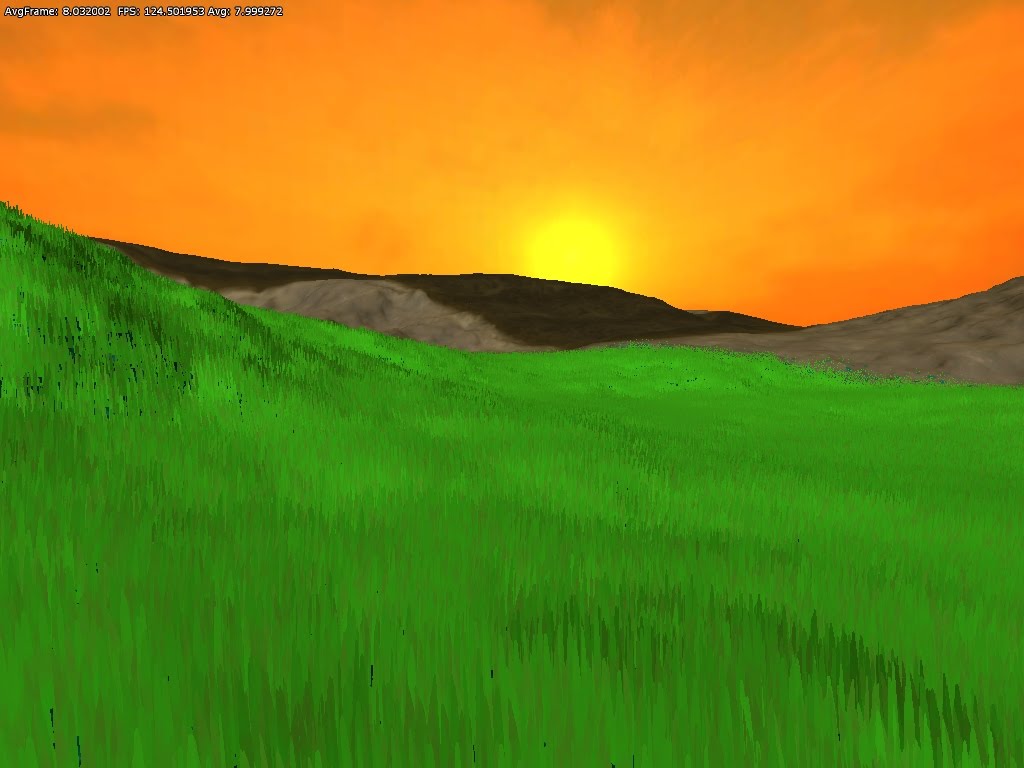

In the above image you can see how the grass dissolves at distance. Here it looks pretty crappy, but with proper art, it is meant that grass and ground texture should match, thus making the transition pretty much unnoticeable.

Another thing worth mentioning, is that the normal for each grass model is the same as the ground. This gives a nice look to many plants, but an individual plant gets quite crappy shading. Undergrowth is meant to be small and not seen close-up though, so I think this should work out fine. Also, when making grass earlier (during development Amnesia), normal normals (ha…) were used and the result was quite bad (sharp shading, etc).

Animation

Static grass is boring, so of course some kind of animation is needed. What I wanted was two different kinds of animation: A global wind animation (unique for each material) and also local animation due to events in a limited area (someone walking through grass, wind from a helicopter, etc).

My first idea was to do all of these on the cpu, meaning that I would need to resend all the geometry to the graphics card each frame. This would allow me to use all kinds of fanciness for animation (like my dear noise and fractals) and would easily allow for lots of local disturbances.

However, I did some thinking and decided that this would be a bad idea. Not only does the sending of data to the graphics card take up time, but there might be some pretty heavy calculations needed (like rotating normals) for a lot plants, so the cpu burden would be very heavy. Instead I chose to do everything on the GPU.

Implementing the global wind animation was quite simple; i was just a matter of sending a few new variables to the grass shader. But it was a bit harder to come up with the actual algorithm. Perhaps I did not look hard enough, but I could find very little help on this area, so I had to do a lot of experimenting instead. The idea was to get something that was fast (i.e. no stuff like Perlin noise allowed) and yet have a natural random feel to it. What I ended up with was this:

add_x = vec3(7.0, 3.0, 1.0) * VertexPos.z * wind_freq + vec3(13.0, 17.0, 103.0);

offset.x = dot( vec3(sin(fT*1.13 + add_x.x), sin(fT*1.17 + add_x.y), sin(fT + add_x.y)), vec3(0.125, 0.25, 1.0) );

add_y = vec3(7.0, 3.0, 1.0) * (VertexPos..x + vOffset.x) * wind_freq + vec3(103.0, 13.0, 113.0);;

offset.y = dot( vec3(sin(fT*1.13 + add_y.x), sin(fT*1.17 + add_y.y), sin(fT + add_y.z)), vec3(0.125, 0.25, 1.0) );

This is basically a couple of fractually nested sin curves (fbm basically) that take the current vertex position as input. The important thing to note is the prime numbers such as vec3(7.0, 3.0, 1.0) without these the cycles of the sin curves overlap and the end result is a very cyclic, boring and unnatural look.

The offset generated is then applied differently depending on the height of the plant. There will be a lot of swaying at the top and none at the bottom. To do this the base y-coordinate of the plant is saved in a secondary texture coordinate and then looked up in the shader.

Now finally, the local animation. To do this entities called ForceFields are used. (Thanks Luis for the name suggestion! It made doing the boring parts so much more fun to make.) These are entities that come with a radius and a force value, and is meant to create effects on the graphics that they touch. Right now only grass is affected, but later on effects on ropes, cloth, larger plants , etc are meant to be added.

These effect of these are applied in the shader and currently I support a maximum of four ForceFields per cache patch. In the shader I either do none, a single entity or four at once. This means that if three entities affect a patch, I still render the outcome of four, but fill the last one’s data with dummy (null) values. Using four is actually almost as fast as using a single. Because of how GPUs work, I can do a lot of work for all four entities in the same amount of instructions as for a single. This greatly cut down the amount of work that is needed.

Again, just like with the global wind, it was hard work to come up with a good algorithm for this. My first idea was to simply push each plant away from the center of the force field, but this looked really crappy. I then tried to add some randomness and animation to this in order to make it nicer. As inspiration, I looked at Titan Quest, which has a very nice effect when you walk through grass. After almost a days work the final algorithm look something like this:

fForce = 1 – distance(vtx_pos, force_field_pos)/force_field_radius

fAngle = T + rand_seed*6.28;

fForce *= sin(force_field_t + fAngle);

vDir = vec2(sin(fAngle), cos(fAngle));

vOffset.xz += vDir * fForce;

Rand seed is variable that is saved in the secondary texture coordinate and is generated for each plant. This helps gives more random and natural feel to it.

Here is how it all looks in action:

And in case you are wonder all of this is ugly, made in 10 seconds, graphics.

End notes

Now that undergrowth is finally done, it means that all basic terrain features are implemented! In case you have missed out on earlier post here is a summary:

I hope this has been of use and/or interest to somebody! 🙂

Next up for me is some final terrain stuff (basically just some clean-up) and then I will move on to more gameplay related stuff. More on that later though…